His 2500 will help you become a better historian, and be able to appreciate, use, and sift the work of other historians. Doing this in the 21st century involves a variety of digital tools, and this course introduces these and teaches you how to use them yourself.

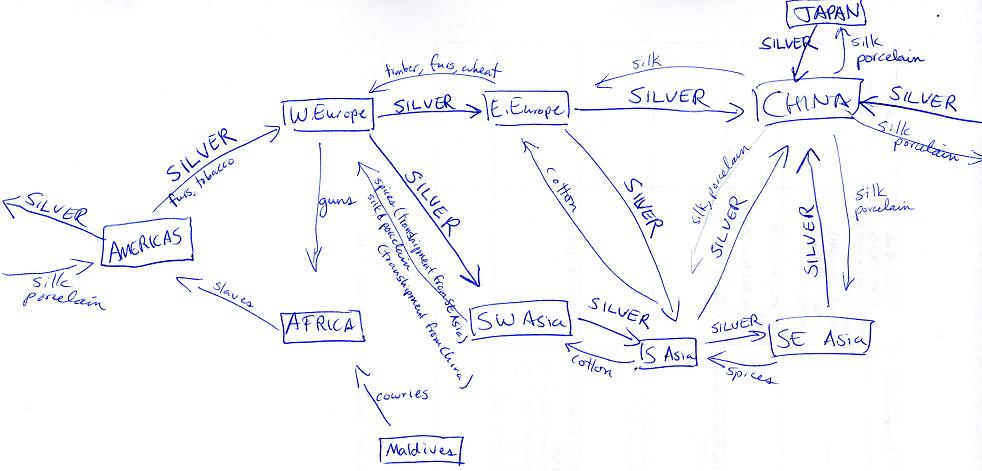

This semester, the course will focus on Global Lines/Lives, 1550-1750. You will be asked to learn about the global interactions during that period (focusing only on the issue/problem you are going to write about), and develop an area of expertise in which you will develop a bibliography and write a brief research paper. But the tools and processes you learn can be applied to the study of most eras from ancient to contemporary history.

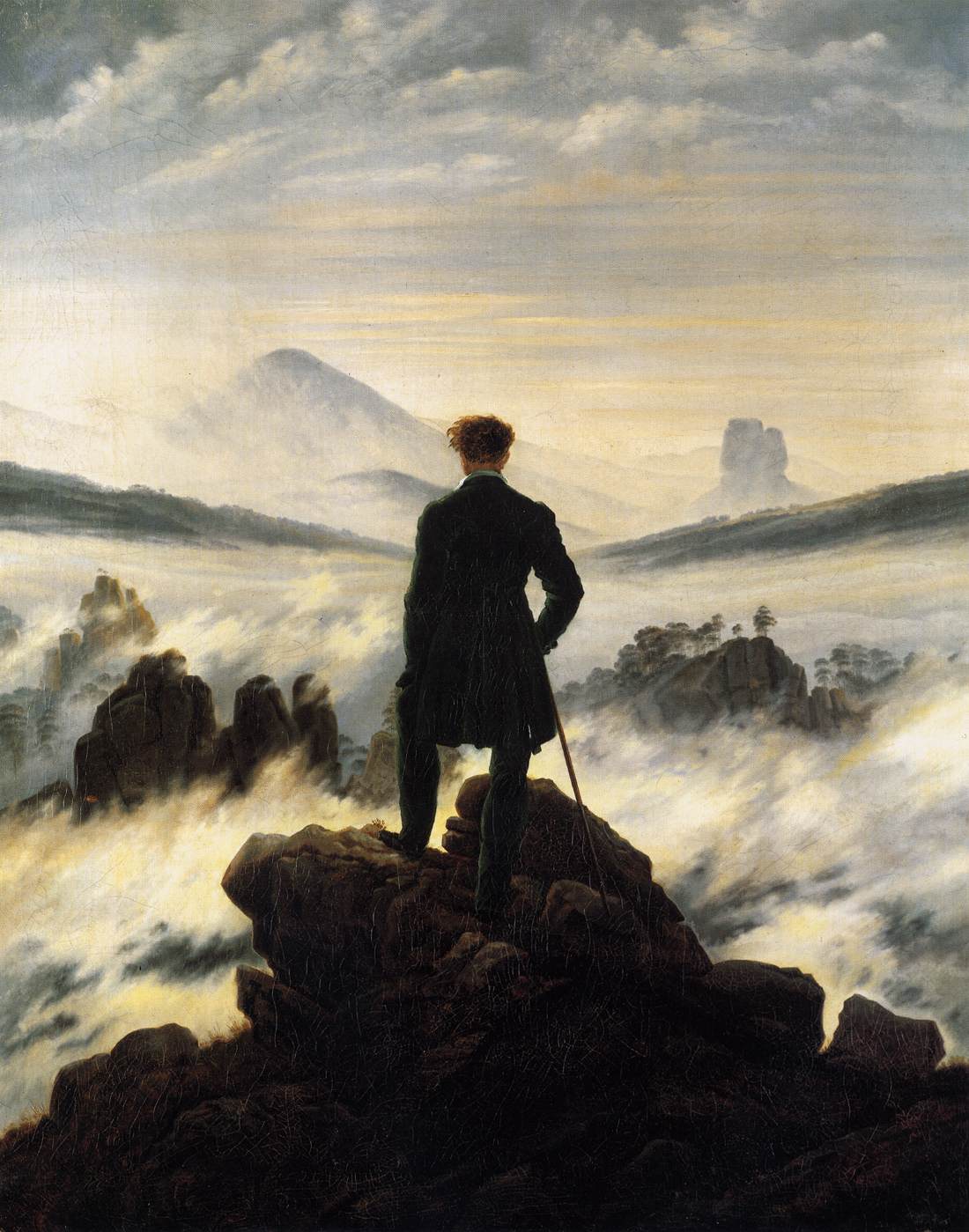

week 1. Introduction. "Professor Trevor-Roper tells us that the historian 'ought to love the past.' This is a dubious injunction. To love the past may easily be an expression of the nostalgic romanticism of old men of old societies, a symptom of loss of faith and interest in the present or future." Edward Hallett Carr, What Is History? (New York, 1961), 29

- 22 Aug. Assignment 1. The Paragraph. Write two paragraphs comparing and contrasting writing history and directing a (historical) film. Due 29 Aug. (full assignments in D2L)

- 24 Aug. I. W. Mabbett, “A History Essay is History” (D2L)

- Rasmus Falbe-Hansen, "The Filmmaker As Historian," P.O.V.: A Danish Journal of Film Studies, 16 (Dec. 2033): 109-12

- "The Duchess" (2008, trailer)

- "The Duchess" - Costume Featurette

- "The Duchess" - Locations Featurette

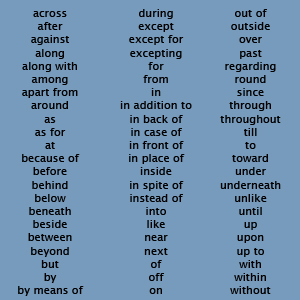

week 2. Revising Prose. "Emphasize nouns and verbs in writing. This means...making them bear the burden of the sentence. Adjectives and adverbs, thus, should be used sparingly. It is obvious that much gooey writing is due to overuse of adjectives." Robert Jones Shafer, ed., A Guide to Historical Method, 3rd ed. (Homewood, IL, 1980), 211

- 29 Aug. Lanham, “The Paramedic Method” (d2l); Assignment 2. The Revision. Revise a coursemate's history statement. Due 31 Aug. (full assignments in D2L); Presnell, I-LH, Introduction

- Ben Yagoda, “The Elements of Clunk,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, January 2, 2011.

- The Paramedic method (Purdue's summary of Lanham)

- 31 Aug. Ogborn, GL chs. 1, & 3 or 4 (as chosen/assigned). Assignment 3. The Word. Use OED (on-campus link only; off-campus go through Booth Library page) and Google NGram to research four related words from Ogborn, GL, ch. 3 or 4 and write an essay on what these words meant in the 17th century and how the meaning of the subject has changed over time. Due 7 Sept. (full assignments in D2L)

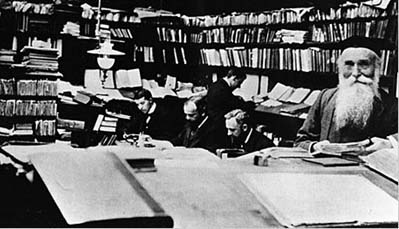

week 3. Words in Context. "Words may have different meanings at different times in history.... Especially when you are dealing with primary sources, it is essential that you know what a word meant at a particular time.... Turn to a dictionary of historical principles, which traces changes in forms and meanings of a word through time. The greatest of these is the Oxford English Dictionary, commonly called the OED. The first edition, originally issued in ten volumes from 1888 to 1928, took fifty-four years to produce, and almost half of its 15,487 pages were written by Sir James Murray, in consultation with thousands of English-language experts around the world." Neil R. Stout, Getting the Most out of Your U.S. History Course: the History Student's Vade Mecum, 3rd ed. (Lexington, MA, 1996), 30-1

- 5 Sept. Lanham, Revising Prose (a review, D2L); Presnell, I-LH, ch. 1.

- Introducing Ngrams

- Introducing Ngrams

- 7 Sept. Ogborn, GL, chs. 3-4 as chosen. Individual meetings

- 12 Sept. (Possibly meet in Reference Room, Booth Library.) Presnell, “Reference Resources,” ch. 2. Assignment 4. The Reference Work. Use works in Booth Library Reference Room (or online sites–not library catalogs) to establish context of one aspect of early modern global connections. Cite reference works and write two paragraphs on points of context (at least five). Then write a paragraph discussing a possible research question about a specific subject suggested by this context. Due 19 Sept. (full assignments in D2L)

- 14 Sept. Definitely Meet in Reference Room, Booth Library. Introducing Zotero.

- Undergrads Should Love Zotero

- Zotero Intro

- Page 99 test

- How to read a book

- John D'Agata and Jim Fingal, "What happened in Vegas," Harper's (February 2012) [from a book entitled, The Lifespan of a Fact; what is proven about the past?; what is not?]

- Assignment 3 (previous years' comments)

week 5. The Historian and the Thesis. "Learn to spot the thesis.... Pay particular attention the first paragraph of each chapter or subheading, because it should contain the thesis. A thesis is a proposition whose validity the author demonstrates by presenting evidence.... (Newspapers call this a 'lead.')" Stout, Getting the Most out of Your U.S. History Course, 5

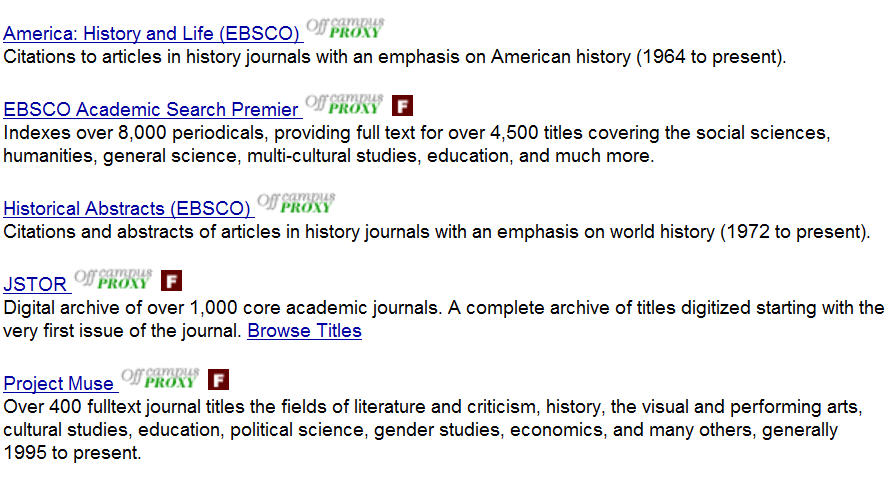

- 19 Sept. Presnell, “Finding Journals...,” ch. 4. Assignment 5. The Index. Using Historical Abstracts, Google Scholar, and Zotero, draw up a bibliography of at least 12 works on a specific subject (use your context sheet and your readings so far to draw up a list of terms related a topic you wish to pursue for your research) and write a paragraph on what has and has not been covered on this subject recently. Due 28 Sept. (full assignments in D2L)

- 21 Sept. Use Zotero, Turabian/Chicago Manual of Style (or as in EIU History Citation Guide) to format a bibliography. Due 26 Sept.

- Pre-Assignment 6a. Taking one article that you are using for Assignment 5 (and another as assigned in class), copy the sentence you think most fully covers the thesis of the article and cite it correctly. Due in class. (full assignments in D2L)

- Zotero & Word

- Boolean Logic & Venn Diagrams

week 6. Types of Historians. "Study the historian before you begin to study the facts." [Carr, What Is History?, 26]

- 26 Sept. Graff and Birkenstein, They Say/I Say, “Preface” & “Introduction” (D2L). Assignment 6. The Thesis Statement. Read any article on your list generated for Assignment 5, cite it correctly, copy the sentence you think most fully covers the thesis of the article, then outline subject, thesis, and subtheses of essay in your own words. (Add your pre-assignments 6a & 6b at end.) Due 3 Oct. (full assignments in D2L)

- 28 Sept. Osborn, GL, ch. 7. Pre-Assignment 6b. Write two sentences only: one stating what the central question is for one historian (to be assigned), another stating what is the answer to that question for the author. Due in class.

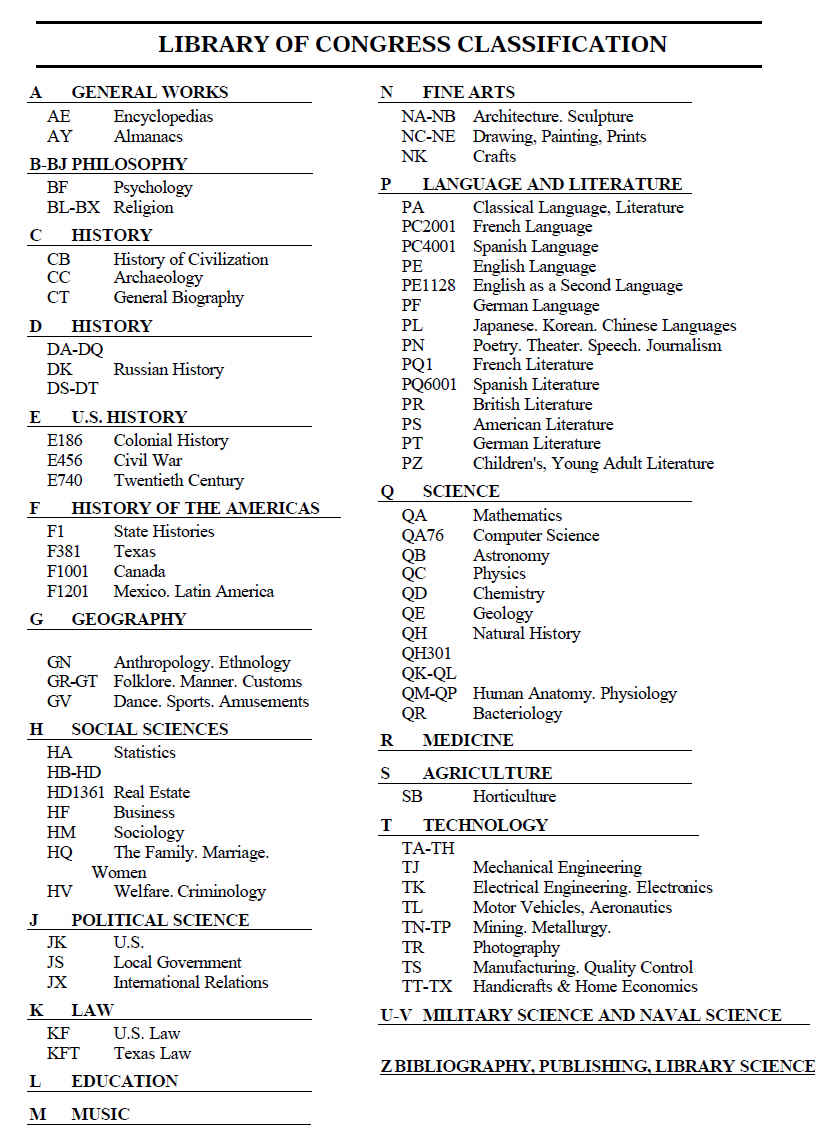

week 7. Constructing a Problem. "Technique begins with learning how to use the catalogue of a library. Whatever the system, it is only an expanded form of the alphabetical order of an encyclopedia. A ready knowledge of the order of letters in the alphabet is therefore fundamental to all research. / But it must be supplemented by alertness and imagination, for subjects frequently go by different names. For example, coin collecting is called Numismatics." Jacques Barzun and Henry F. Graff, The Modern Researcher, 5th ed. (Fort Worth, 1992)

- 3 Oct. Presnell, I-LH, ch. 3. Assignment 7. The Problem/Hypothesis. Using the online catalog, construct a bibliography (at least 12 secondary works available in Booth Library) focusing on a specific research problem relating to early modern Global Lines/Lives. Then using this bibliography, write an essay about a possible research subject. Include a paragraph with a possible thesis statement for your research paper. Due 10 Oct. Meet in eClassroom Booth Library. (full assignments in D2L)

- 5 Oct. Pre-Assignment 7a. The Shelfie. Find one work from your list for Assignment 7 in Booth Library. Take a photo of the books on the shelf in which it is found. Draw a Venn diagram of how those books are related. Due in class. Meet in 1116 Booth Library.

from Luke Clossey, Simon Fraser University

week 8. The Document. "What makes a historian master of his craft is the discipline of checking findings, to see whether he has said more than his source warrants. A historian with a turn of phrase, when released from this discipline, risks acquiring a dangerously Icarian freedom to make statements which are unscholarly because unverifiable." Conrad Russell, cited in Mark A. Kishlansky, "Saye No More," Journal of British Studies 30 (Oct. 1991): 399

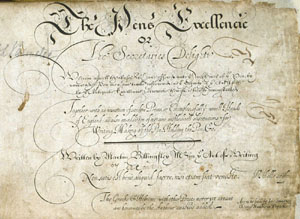

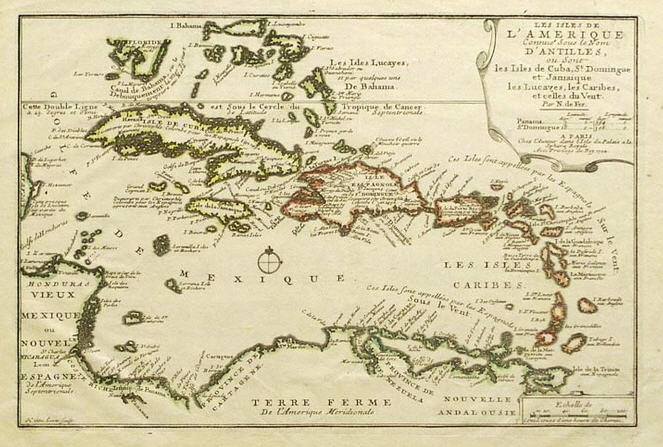

- 10 Oct. Presnell, I-LH, ch. 5. Assignment 8. The Document. Using EEBO find a 17th-century title page, woodcut/illustration/map, and 10-pages of a printed primary source, and compare and contrast these in a brief descriptive essay. Due 17 Oct. (full assignments in D2L)

- 12 Oct. Primary sources (to be assigned).

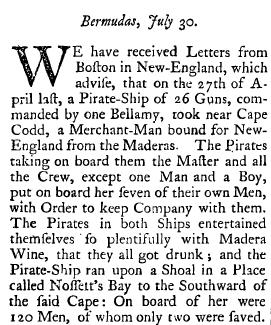

week 9. The Newspaper or Serial Source. "[H]istory is to a considerable extent a matter of numbers. Carlyle was responsible for the unfortunate assertion that `history is the biography of great men.' But listen to him at his most eloquent and in his greatest historical work: ‘Hunger and nakedness and righteous oppression lying heavy on 25 million hearts: this, not the wounded vanities or contradicted philosophies of philosophical advocates, rich shopkeepers, rural noblesse, was the prime mover in the French revolution; as the like will be in all such revolutions, in all countries.’" [Thomas Carlyle, French Revolution, cited in Carr, What Is History?, 61]

- 17 Oct. Presnell, I-LH, ch. 6. Assignment 9. The Edited Collection or Serial Source. Identify a set of published papers in Booth Library relevant to your topic; or read a set of online 17th-century newspapers related to your topic. Read the pertinent documents and write a brief paper, with foot or endnotes, analyzing how the published papers relate to the view of the topic advanced by Ogborn. Due 24 Oct.

- 19 Oct. London Gazette. Paleography exercise (Pre-assignment 9a) focusing on 17th-century newsletters. (To be explained.)

(Also, another Library of Congress classication chart)

week 10.The Edited Collection (and using Voyant). "The critical traits of an archival resource for historians include custodianship and proper sourcing, and the critical traits of an online presentation of historical artifacts parallel those: care of the digital resource and clear provenance.” [Sherman Dron, “Is (Digital) History More than an Argument about the Past?,” in Writing History in the Digital Age, ed. Kristen Nawrotzki and Jack Dougherty, 2013]

- 24 Oct. Presnell, I-LH, ch. 7.

- 26 Oct. Secondary source (to be assigned).

week 11. Developing a Treatment. "Hollywood producers, with millions of dollars at stake, require writers to produce `treatments' of proposed movie plots. These short sketches of the film plot enable both the writer and potential producer to see the story in a nutshell. In the same way, you can test the potential of history paper topic by writing a one-paragraph treatment." [Pace and Pugh, Studying for History, 181]

- 31 Oct. Pre-Assignment 10a. Storyboarding. (To be explained.) Due In class. Assignment 11*. The Research Paper. Write a research paper on early modern Global Lines/Lives using at least three types of primary sources, making an argument, and responding to what other historians have said about your subject (that is, using several secondary works for both context and argument). Draft Due April 18; revision due May 2.

-

2 Nov. [No class.] {All students should have conferenced with me individually between 17 and 31 Oct.}

- London Gazette (advanced search)

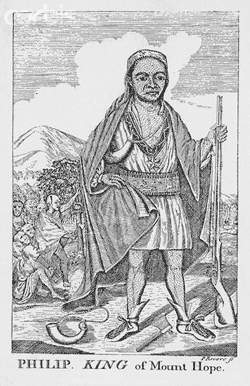

- Converting EEBO Zotero bibliography to final draft (North American Indians example)

Edward Collier, "Still Life" (c. 1680s)

week 12. Research and Writing. "History and writing are inseparable. We cannot know history well unless we write about it. Writing allows us to arrange events and our thoughts, study our work, weed out contradictions, get names and places right, and question interpretations–our own and those of historians.” [Richard Marius and Melvin E. Page, A Short Guide to Writing About History, 4th ed. (New York: Longman, 2002), 6]

- 7 Nov. Presnell, I-LH, ch. 11. Secondary source (to be assigned).

- 9 Nov. Marius, Short Guide, ch. 6. (D2L) Assignment 10. The Note. Write a two-page treatment (see handout) about just one part of your research paper which is buttressed by at least four foot or endnotes, including a content note and two from the same source. Due 14 Nov. Note Quiz I.

week 13. Writing and Noting. "Footnotes exist...to perform two...functions. First, they persuade: they convince the reader that the historian has done an acceptable amount of work, enough to lie within the tolerances of the field.... Second, they indicate the chief sources that the historian has actually used. Though footnotes usually do not explain the precise course that the historian's interpretation of these texts has taken, they often give the reader who is both critical and open-minded enough hints to make it possible to work this out–in part. No apparatus can give more information–or more assurance–than this." [Anthony Grafton, The Footnote: A Curious History (Cambridge, Mass., 1997), 22-3]

- 14 Nov. Readings based on individual research.

- 16 Nov. Note Quiz II.

<

<week 14. Revising. A Checklist for Revising:

- “Does what I have written support my thesis?" [If not, change the thesis.]

- “Are things in the right order?" [Moving blocks by computer is easier than cut-and-paste. Do it.]

- "Is every item necessary?" [Irrelevant words and anecdotes "must be killed."]

- "Is any direct quotation, particularly a long one, really essential?" [A good test is whether, and to what extent, you refer to the quote within the paragraph it is placed. If not, usually delete or moved it] [Stout, Getting the Most out of Your U.S. History Course, 68-9]

- 28 Nov., 30 Nov. Paper reports.

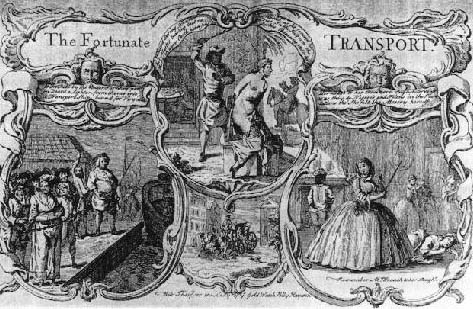

(1741)

(1741)

week 15. Everyman His Own Historian. "Instead of writing this kind of narrative history, most academic historians, especially at the beginning of their careers, have chosen to write what might be described as analytic history, specialized and often narrowly focused monographs usually based on their PhD dissertations.... Such particular studies seek to solve problems in the past that the works of previous historians have exposed, or to resolve discrepancies between different historical accounts, or to fill in gaps that the existing historical literature has missed or ignored.... Their studies, however narrow they may seem, are not insignificant. It is through their specialized studies that they contribute to the collective effort of the profession to expand our knowledge of the past." [Gordon Wood, “In Defense of Academic History Writing,” Perspectives on History (April 2010)]

- 5 Dec. Papers reports.

- 7 Dec. Summing up.

- 11 Dec. 8:00-10:00, Monday, FINAL EXAM

Issued by Textbook Rental:

- Ogborn, Miles. Global Lives: Britain and the World, 1550-1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008. [11.060]

- Presnell, Jenny L. The Information-Literate Historian: A Guide to Research for History Students, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013. [11.000]