Mongrel Tongue

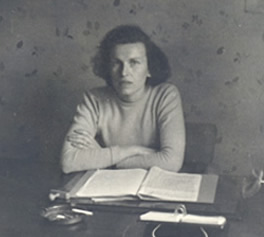

My mother’s English was always better than my father’s. It was a point of pride. My father earned more money at the engineering firm where both worked, he as an engineer, she as a draftswoman. His sense of direction was keener. He may have even spoken Lithuanian with more precision and finesse (though this was a matter of ongoing debate), coming as he did from the Aukstaitija region of the country. But she, my mother, spoke the better English.

My father conceded this point, somewhat reluctantly, arguing that my mother was more fluent because she talked more. She was always talking, talking, talking, blurting out whatever was on her mind. Like most Lithuanian women.

“I’m just naturally gifted when it comes to languages,” my mother would answer.

And who could argue? Her German was even better than her English, her French passable, her Russian enough to allow her to read the simpler poems of Pushkin.

What she failed to mention in these conversations, however, were her early advantages, the good schools and the expensive books and the maid that freed my mother from household chores. Her father was the principal of a prestigious private high school in Kaunas. The artifacts of my mother’s life attest to privilege: an emerald necklace lost while playing in the woods of Marijampole when she was nine; shoes the color of cherries bought on a trip to Stockholm; Agatha Christie paperbacks read at night with the flashlight beneath her blanket, on constant watch for my grandmother, who believed that a good night’s sleep was vital for mental health and the proper regulation of the menses.

My father’s parents were subsistence farmers, living from day to day on potatoes, apples, and mushrooms, harvesting wheat when the summers obliged. Politically the family leaned to the left—my father’s father read the Social Democrat and frequently praised the revolution, walking around the little house singing the Marseillaise in broken, perverted French. The neighboring farmers called him a bolshevik, though my father suspects that this had less to do with political beliefs than with the fact that his father rarely went to church and often appeared at the dinner table having forgotten to remove his cap—both clear signifiers of advanced and irreparable bolshevism.

English wasn’t even an option for my father in the two-room wooden school house on Kazys Buga Street in Dusetos, now a shoe repair shop.

Another reason my mother spoke the better English was that she wasn’t afraid of questioning the meanings of unfamiliar words and phrases. It takes a certain sense of entitlement to expect—demand—clarification in a country whose language and customs are not your own. She asked gas station attendants to explain the difference between juncture and junction. She asked the grocer why milk was labeled homogenized when it was obvious that all milk was the same. She asked me the meaning of posh and petulant and vitriol, and what a prosthetic device was.

Once, walking down Rush Street, on the way to I don’t know where—what could we have been doing walking down the seedy part of Rush Street together—she pointed to a sign:

“What does that mean?”

“What?”

“Peep show,” she said slowly, loud enough so that several people turned their heads.

I didn’t know what to say. How to translate peep show?

Several years ago, on a flight to Washington, D.C. where I was to make a presentation at my first major conference, my mother nudged me as I was proofing my paper. She pointed to a word in the Glamour I had bought at the airport.

“What does this mean?”

“What?”

“Dildo.”

"I'm not going to explain this to you just right now, mother."

"Perhaps I can ask that nice young steward."

"Mom!"

“I’m just kidding.”

Although my mother’s English was better than my father’s, she spoke to my sister and me in Lithuanian when we were girls. She did this not only at home, but in public—in stores, on the street—oblivious to the occasional stares we received from strangers. In this she was different from my father, who insisted on English in the presence of non-Lithuanians. Once, on a

vacation to the Grand Canyon, looking through the stand-up binoculars where for a dime (back then) you could watch for a minute or two the very crevices at the bottom, I called to my sister Rita to come look: ateik, ateik.

"Vee cow-moon-ick-ate in English," my father said.

"Are you ashamed of your heritage?" I asked him, in Lithuanian.

"Ah you ashamed of yo con-tree?" he shot back.

I mentioned an Ann Landers column about taking pride in speaking one's native language. My father, who read and admired Ann Landers, was nonetheless adamant: Vee cow-moon-ick-ate in English.

The irony, of course, was that my father’s vocal, overly enunciated English marked him as a foreigner in a way that a quiet, natural Lithuanian would not have. He plowed ahead, oblivious to articles, ignoring the dangers lurking in prepositional phrases. When my American friends would visit, my father would greet them with “How you do?” How you do, Lisa? Say, Tom, how you do? After one too many How you dos, I couldn’t take it anymore. I began to yell: “It’s not How you do? It’s How do you do? How do you do, dad? How do you do?”

Although my mother spoke the better English and was not afraid to ask the meanings of words she didn’t know, she often insisted on her own interpretations, shrugging away my corrections with a wave of her hand.

“I almost married a business mongrel,” she once told me.

“You mean business mogul.”

“I could have lived in the lab of luxury.”

I envisioned a large white room where well-heeled women mixed vials of precious oils to create Chanel No. 5, where men wearing Armani ties peered under microscopes to examine the inner workings of expensive Swiss watches.

My mother and I are sitting in Jedi’s Garden, a restaurant near the Oak Lawn hospital where she has been a regular visitor for the past six months. We switch from English to Lithuanian, interspersing words from one language into another as thoughtlessly as a child baking a cake

from two different recipes.

“How are you, mama?”

“My wanes hurt,” she tells me, flexing her arm.

“Your John Waynes?”

“The nurse took some blood.”

She barely touches her rosemary chicken, plays with the carrots in her vegetable medley.

“Valgyk,” I say.

She doesn’t eat, but finishes her glass of red wine.

“Another one?”

“No. I don’t want people to think I’m some kind of a slush.”

As she sees her life closing in on her, her appetite disappearing with each diminishing white cell, my eighty-four year old mother relies on memories of the past to keep her grounded in the living. She talks about her mother, whose first language had been Polish, the mother tongue of the Lithuanian nobility. She’d perfected her already fluent Russian in St. Petersburg, where she studied physics and geography. It was at the university, a meeting of the young Lithuanian Socialist League—St. Petersburg Chapter—that she met her future husband, my grandfather, the oldest son of wealthy farmers.

My mother talks about the handsome Frenchman.

“Did I ever tell you the story of the handsome Frenchman?”

“You mean the handsome Frenchman who left his beautiful French girlfriend for plain ol’ Aldona Markelis?”

“Yes, that handsome Frenchman. The girlfriend, she really was very beautiful. But also very angry.”

“How angry was she, mom?”

“She was so angry she hit me with a shoe.”

Most of all, however, she talks about my father, whom she met at a party of raucous Lithuanians on the south side of Chicago in the mid 1950’s. She was walking around with a glass of wine in her hand, reciting a poem: “Burn me, like a witch, burn me in blazing fire…”—by the revolutionary Lithuanian poet Salomeja Neris.

My father took one look at my mother holding her wine glass as if it were the torch on the Statue of Liberty and fell in love.

It took my mother longer to see the light.

“He’s short,” were the first words my grandmother uttered when my mother brought him home to meet the family.

But my father bought my mother flowers, and he owned a car, and, besides, at thirty-seven she was not getting any younger.

They never would have met in Lithuania. Or, if by some capricious accident of destiny they’d had, my mother would have fled to Kaunas at the sight of my grandfather shoveling hog manure, of my grandmother with her babushka muttering from her tattered little book of prayers.

Reading was my parents’ strongest bond, the milky glue that helped cement their sometimes tenuous allegiance. They disagreed on money and the principles of child rearing. My father would withdraw into himself, closing like a fist; my mother would cry. Evenings, their bedroom door half-open, I would hear voices falling and rising, the rhythmic ta-da, ta-da of Lithuanian sentences, followed sometimes by extended silence, sometimes by laughter.

The waitress comes to check on us.

“Can I take that for you, hon?”

“No. But I would like a dog bag.”

The waitress smiles.

“I wish I had a camera with me,” my mother says.

“Why?”

“To take a photograph of your laugh.”

In a minute they’re chatting away as if they’re soul-mates. My mother tells the waitress that she’s from Lithuania. The waitress compliments her English and soon discovers that my mother’s English was always better than my father’s.

“Does anyone ever ask for a cat bag?” my mother wants to know, a reasonable request “because cats need goodies too.”

The waitress, who owns a tabby, concurs, but adds that cats are more selective: “Dogs, you can give them anything.”

“Yes, dogs are like that,” adds my mother. “Our dachshund, Nika, we named her after Nikita Khrushchev, she once grabbed a frozen steak out of the refrigerator when no one was looking.”

As my mother pays the bill, the waitress says goodbye.

“Sudiev,” my mother answers. Then: “Aufwiedersehen.” Finally, for good measure: “Au revoir.”

“Have a nice day,” I wave.

My words feel flat and lifeless, my farewell as uninspiring as a sack of Lithuanian potatoes.