This is a close-up photograph of an aphanitic, or fine-grained

basalt. Note the lack of any very well-defined

crystals.

That's because it cooled very quickly and crystals didn't have a chance

to form. About the only crystals you may see in this basalt

are lath-shaped (rectangular) plagioclase that are whitish. |

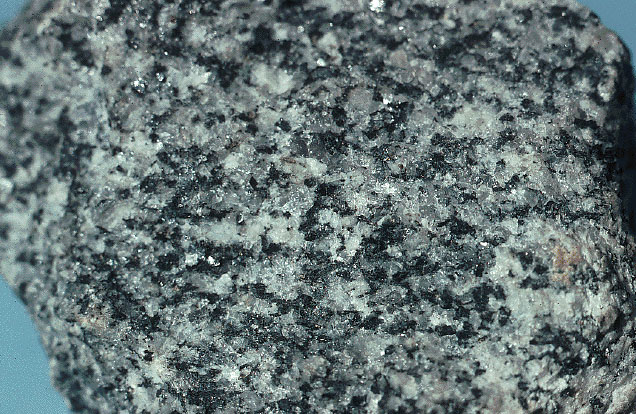

A close-up of a medium-grained gabbro.

Compositionally

the gabbro is the same as the aphanitic basalt, but it

took

a longer time to cool - hence the better developed crystals. The

crystals in the gabbro are the light-colored plagioclase and

the

dark-colored olivine and pyroxene. |

Close-up view of a fine-grained granite. Note the lack

of large crystals. Since the crystals are small, this granite

probably cooled relatively quickly before they had a chance to

grow.

One possible location might be near the edge of the magma chamber,

close to cool country rocks. |

Again, this is a granite, however, this time it is coarse-grained

indicating that the crystals had a much longer time to

crystallize.

This rock may have formed further towards the center of the magma

chamber

where it was warmer and more insulated for a longer

time. Also

not the zoned plagioclase feldspar crystals, they're the

pinkish

crystals. The smoky, or gray, crystals are quartz, and

the

black crystals are biotite. |

This is a medium-grained granite. The size of the

crystals

indicates that it took longer to cool than the fine-grained granite

above,

but shorter to cool than the coarse-grained granite above and

to

the right. The minerals found in this are the same as the other

granites. |

This is an extreme close-up of one of the zoned plagioclase feldspar

crystals seen in the coarse-grained granite above. Note

the

rings around the center of the plagioclase crystals. Like rings

found

in trees, these rings are placed on the outside edge of the crystal as

it grows. The rings indicate that the magma, or melt, was

slowly changing its composition, and hence color, as the rest of the

crystals

formed. This is very common in crystals that took a long time to

form. |

If the magma forming an igneous rocks fragments, or cools

quickly

and explosively, it may produce pumice, a

pyroclastic

rock. Pumice is very porous and will sometimes

float on

water. Here we can see a very thick layer of pumice. |

If a magma cools extremely rapidly, quenched, then it may form an obsidian.

Not all obsidian is black. Colors range from black to

brown,

to red, to green to blue and yellow. This particular obsidian is

called mahogany obsidian because of its color. Obsidian also

exhibits

conchoidal fracture which is the smooth, curved surfaces

seen here

and also found in quartz. |

If the lava or magma has some vesicles, or gas

bubbles, in it, but is not as lightweight as pumice and does

not

float in water, then we call the rock scoria. It is

generally

darker than pumice and may have a few small crystals of olivine

or plagioclase visible. |

An extrusive rock that is compositionally the same as granite

is a rhyolite. Since it is extrusive it implies

that

it cools very quickly and we would not normally see crystals.

This

particular example is a rhyolite in which the magma

started

to cool slowly, and crystals started to form. It was then erupted

and quenched - stopping crystal growth. This texture of both

large

crystals (phenocrysts) and small crystals, or none, in a fine-grained

matrix (groundmass) is called porphyritic.

Therefore

this would be a porphyritic rhyolite. Note the zoned

plagioclase. |

Sometimes when an igneous rock intrudes the surrounding country

rocks it does so in a brittle manner. That is, it doesn't

just

flow into cracks and joints that it makes. Here we see dark country

rock (older basalt) that has been torn apart as the granite

was intruded. The broken basalt fragments are called xenoliths.

Xenoliths allow us to use the Principle of Inclusion

to tell

in a relative sense which rock is older - here the basalt is

older

than the granite. |

If an intrusive igneous rock does not cut across the

surrounding

rock's fabric, or bedding, then we call that a concordant intrusion,

or a sill. |

An

intrusive igneous rock that cuts across, or is discordant

to, the surrounding rock's fabric (bedding) is called a dike.

Here we see a 1 meter thick basalt dike. An

intrusive igneous rock that cuts across, or is discordant

to, the surrounding rock's fabric (bedding) is called a dike.

Here we see a 1 meter thick basalt dike. |

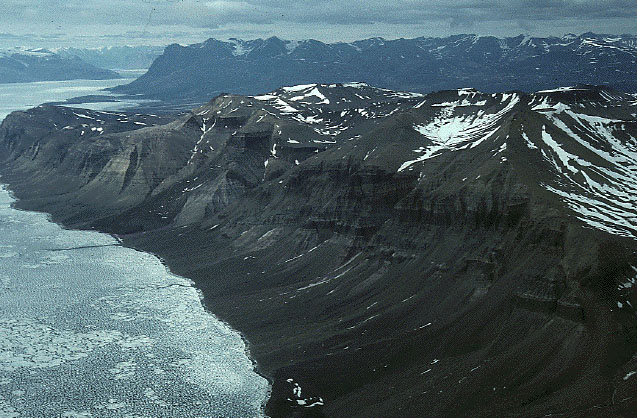

These are igneous sills that have been faulted. Not the

upper most land surface continues uninterrupted, whereas the igneous sills

have been offset along a fault. We will talk about what type of

fault

this is in later chapters. |